Platformization of Science Communication: Are We All Influencers?

How social media platforms have changed science communication and the implications of this process for the academic profession

Science communication is the practice of informing, educating, and raising awareness about scientific discoveries and arguments. In the highly influential definition of science communication, Burns, O’Connor and Stokcklmayer (2003) proposed the AEIOU analogy to define science communication in terms of its goals: Awareness, Enjoyment, Interest, Opinion-forming, and Understanding. Science communication refers to the ability to discuss science in ways that audiences understand and takes various forms such as documentaries, podcasts, science journalism, blogs, books, and science museums. In the last decade, science communication increasingly comes in the form of visual and textual posts on social media platforms.

Platformization

With the emergence and consolidation of social media platforms and the rise of what Nick Srnicek has called "platform capitalism" science communication increasingly takes place on social media platforms. Interactions of academics with social media platforms could be understood as a process that Anne Helmond (2015) has called platformization. In the field of cultural production, Poell, Nieborg and Duffy (2021) define platformization as the penetration of digital platforms' economic, infrastructural, and governmental extensions into the cultural industries, as well as the organization of cultural practices of labor, creativity, and democracy around these platforms. Replace "science communication" with "cultural industries" and you get the definition of platformization of science communication.

The platformization of science communication has been around for at least a decade. Twitter is an important medium for scientists to share their texts, arguments, and publications. As early as 2014, one researcher mockingly developed the "Kardashian Index" to measure the popularity of scientists based on the number of followers they have on Twitter. More recently, the rise of TikTok has given new impetus to the platformization of science communication, as the rules for what content can be successful on TikTok are much looser than on other social media platforms such as Instagram. Unlike the latter, TikTok does not require polished lifestyle content to reach an audience. What counts there is the discursive quality of the content, which allows for more diverse presentations of the self. With this "democratization" of content, we are witnessing the rise of the platformization of science communication. We watch TikTok videos from expert influencers in the fields of medicine, social sciences, health, chemistry, and many others debunking myths about their professions and sharing research findings under the hashtags #ProfessorsOnTikTok, #LearnOnTikTok, and #SciComm. These expert influencers are often celebrated for fighting the windmills of dis- and misinformation in the penumbra of social media.

Academic Profession Amidst Platformization

Scholars becoming increasingly dependent on social media platforms to reach their audiences and communicate their findings has implications for the substance of the academic profession. In the classic now-more-than-century old public lecture Science as a Vocation, Max Weber focused on the demands, risks, and duties of a scientist and argued that an academic profession requires full dedication. In the lecture, Weber asserted that academia was not a comfortable career choice, it does not bring material rewards, and does not confer meaning or personal happiness to life. Weber also warned against empty careerism and the pursuit of personal fame. He famously claimed that one must have a calling for an academic career, a vocation for a vocation. It is worth bearing in mind that Weber's lecture was a moment in the history of higher education. In this context, he implicitly warned against the "Americanization" of university life: the imposition of audit culture, the constitution of students as customers, and the encouragement of professors to become crowd-pleasing entertainers.

Today, many of Weber's warnings have come true. Social media researcher Brooke Erin Duffy recently underscored how "influencer culture" has become part of academia as its denizens are forced to promote themselves and seek validation through metrics and engagement on social media platforms. Sophie Bishop described the self-promotion that has become an integral part of all forms of work as "influencer creep" which she describes as the feeling that you have not done enough for social media platforms, that you can be more on-trend, more authentic, and more responsive. My aim here is to illustrate how the platformization of science communication has changed the substance of the academic profession, as scientists develop new roles because of the affordances of social media platforms.

Autoethnography

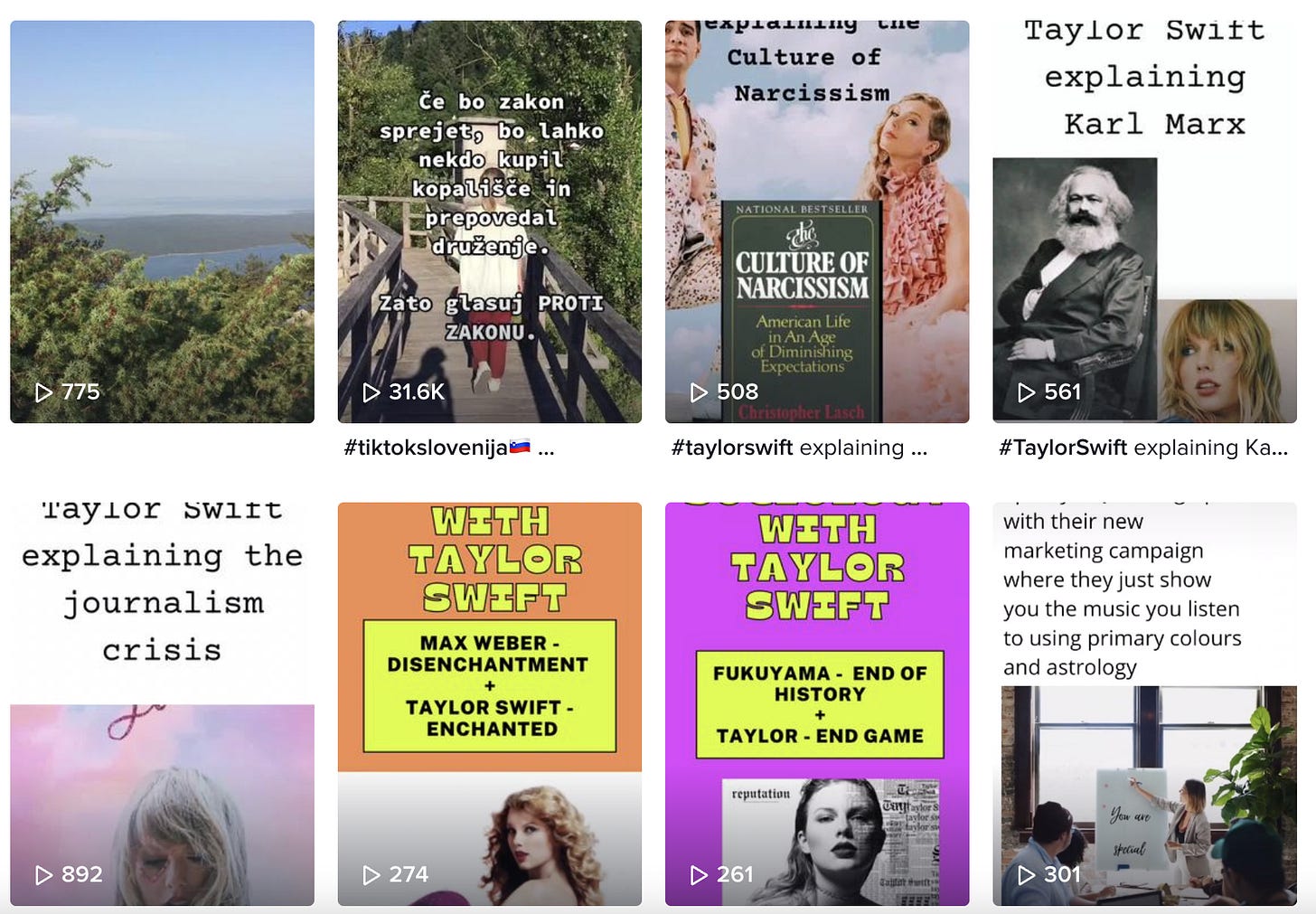

The article draws on autoethnography, a qualitative research method in which the researcher is the primary data collector and interpreter of the meaning of the data. I will elucidate my own experience with creating short videos to explain sociology on the social media platform TikTok. Before I delve into the results, a little background is needed. Why would an overloaded PhD student spend her precious time creating TikTok videos, you might ask. The answer is in my doctoral dissertation, in which I examine the working conditions of influencers in the Balkans and their experiences of being governed by algorithmic systems. During the research process, I learned that it would be productive to become an influencer myself, to be able to talk to my research participants, to "walk their walks and talk their talks". However, doing makeup tutorials and sharing my daily life is not my cup of tea. Hence, I decided my angle would be sociology. After months of being an influencer, I learned that I had accidentally become a (social) science communicator on TikTok. Since October 2021, I have been writing notes about my experiences and these notes serve as the basis for the results.

Hollywood Production in One, Grappling with Metrics, and Developing Algorithmic Imaginaries

To produce videos on TikTok, I had to wear many hats at once: I had to become an (amateur) actor, director, scriptwriter, and location scout, embodying a Hollywood production studio all in one person. I also had to develop completely new skills like video editing. As for the temporal dimension, producing educational TikToks was very time-consuming. I had to schedule specific shooting times, which were mostly on weekends, which extended the sum of hours I dedicated to my job.

Although my influencer efforts on TikTok were largely experimental, I experienced sincere feelings of frustration and anxiety when my videos did not perform well in terms of metric success, number of views, likes, and comments. For example, when my videos were not doing well, I would switch their access to private mode so only I could see them because I was embarrassed in front of my imaginary audience that my content was not doing well. Moreover, I used the feedback on my videos to determine my future content strategies. I quickly learned that sociology without a real person's face was not as interesting as, say, dance or prank videos with which I competed for attention.

In order for my content to perform well, I have developed theories about what content performs well and what does not. In other words, I have developed "algorithmic imaginaries”. I learned that 100-year-old sociological concepts do not interest people or algorithms. What they care about are 1) lifestyle topics and 2) polarizing themes. Because of these imaginaries, my content production moved from science communication to lifestyle communication, which is more in line with the practice of self-promotion. I began promoting myself and my personal experiences of being a PhD student rather than sociology as was my initial plan. Based on the second imaginary, that polarizing themes work well, I moved from science communication to clickbait communication. For example, the video about the referendum on water privatization in Slovenia performed well which informed my future content creation that was more in line with clickbait polarizing communication.

The temporal dimension of TikTok video form means that content and the substance of the content, in my case, sociology, has to move fast (and break things 😝). This, in turn, means that content is stripped out of nuance to the bare bones of definitions, leaving out any corrobations and “baroque” in the theories. It impels one to create content that is discursively impoverished and inclined to black and white positioning, where everything is either/or. McKenzie Wark said this much better than I am: “There’s too many content creators and not enough form destroyers.”

Academic-cum-influencer?

In his classic lecture Science as a Vocation, Max Weber asserted that science requires full dedication, "a calling" for an academic profession. Amid the recent platformization of science communication, it seems that the academic profession today requires a calling not only for science, but also a calling to become an influencer: to embody a Hollywood production in one, to grapple with metrics, and to develop algorithmic imaginaries. Practices that were once part of the work of influencers have become part of the work of academics seeking to promote science in social media.

These academic cum influencer activities result in what Ian Bogost has called "hyperemployment" where we work for our employees but also provide free labor for social media platforms and their profits. Hence, the defining characteristics of science as a profession have changed. These changes resemble Weber's warnings about what science as a profession is not: self-promotion, careerism, the pursuit of personal fame. These changes in the academic profession have a longer history, but platformization has given them new impetus, as platform features require academics to behave in self-promotional way because in the ecosystem of social media platforms, the academic becomes one of the many influencers trying to make their content visible and compete with the voices of gamers, journalists, lifestyle influencers, bots, conspiracy theorists, and many others.

However, the platformization of science communication also has many positive effects.

Thanks to my TikTok account, I have been able to reach out and build rapport with my research participants, cultivate a very small but no less important community of people around my profile, and educate my audience about important sociological topics.